The Advertising Standards Authority's July publication of a report on gender stereotyping in ads sparked a minor media kerfuffle. The ASA's goals are straightforward - harmful stereotypes, its report says, "can restrict the choices, aspirations and opportunities" of people who suffer from them. Advertising, in its view, has played a part in spreading these ideas, and has a future role in preventing them. Reaction divided among familiar lines - campaigners welcomed the move, while the right-wing press fulminated about busybodies and political correctness. But beyond the predictable culture-war responses, the debate has the power to uncover interesting assumptions about how ads work, and who they should appeal to.

To understand what the ASA's proposed regulations mean, we need to understand why advertisers have used gender stereotyping in the first place. There are three main motivations: they do it unconsciously, they do it lazily, or they do it deliberately.

Unconscious stereotyping is in some ways the hardest to fight. Once a gender stereotype has become so ingrained in our consciousness that we accept it automatically, it's difficult to shift. In recent years, psychologists like Daniel Kahneman have shown that the human brain has two modes of decision-making. System 1 makes decisions rapidly and instinctively using simple rules of thumb - like the "Availability Heuristic": if something comes readily to mind, it's a good choice. System 2 can act as a check on System 1's choices, by bringing more considered calculations to bear. But, in general, it waves them through - Kahneman calls it a "lazy policeman".

The availability heuristic can turn easy choices into rock-solid social norms, even stereotypical ones. The idea that pink is a colour for girls only began to dominate in the late 19th century: now it's inescapable, and one focus of campaigners' ire. The indulgence of this stereotype by advertisers can be harmful - one study of breast cancer campaigns found that over-use of pink actually reduced donations from women. The emphasis on gender led to a ‘backfire effect' and caution and denial took hold.

In his book Thinking, Fast And Slow, Kahneman describes how to work against System 1 when it makes an automatic, but bad, choice. The best way is to let a third-party or neutral arbiter check the decisions. This is the role the ASA is playing as a regulator, saving advertisers from unconscious prejudice.

But a lot of gender stereotyping isn't unconscious, it's just lazy, and rather than pandering to System 1 thinking, it arises from a complete misunderstanding of how we make decisions.

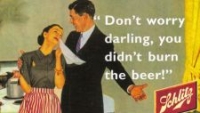

Advertisers, after all, have known for ages that sexist ads are clichéd. There's even a bit of adland jargon for those commercials where two women breathlessly talk about a new cleaning brand or product; ‘2CK' or ‘2 Chicks in a Kitchen'. And the reverse stereotype, where a hopeless man is incapable of doing household chores without some miracle product or other, is just as lazy.The reason brands used such techniques for so long is that they were never the real point of the ad - the actual purpose was to get a rational message over about the effectiveness of a particular product. The stereotypes were just a way of wrapping the iron fist of that message in a ‘velvet glove' of dubious humour. In recent years, though, there's been a major shift in how advertisers see the role of emotion and humour in their work. Two analysts, Les Binet and Peter Field, sparked the shift with a series of books analysing thousands of case studies for the IPA (Institute of Practitioners in Advertising). They looked at the strategies advertising campaigns used, and the real business effects they achieved: tangible gains like profit growth and share gain, not just short term sales boosts.

What they found was remarkable. Purely emotional campaigns were far more likely to lead to profitable growth than ‘velvet glove and iron fist' mixed-mode work. And over the long term, the gulf widened even more dramatically. Message ads were simply not as profitable or effective as emotional ones. Emotion wasn't a Trojan horse to deliver the message - it was the entire point of great advertising.

Why is emotion so important? The answer, once again, is System 1 thinking. One of the major short-cuts System 1 uses to make judgements is the Affect Heuristic - if we feel good about something, it's a good choice. The lift created by positive emotion helps guide and simplify decisions, and that includes brand decisions. In a purchase situation we almost certainly won't spontaneously remember the product claims made for a brand. We will, though, react well towards it if its advertising has made us feel happy and created positive emotions.

This is good news for advertising creativity, and bad news for lazy stereotyping. Stereotypes don't tend to create positive emotion - after all, they're alienating half the potential audience, and by their nature they are over-familiar. At System1 Research we test ads for the emotional response they generate. In a decade of testing thousands of ads, we've seen dozens of very high-scoring, deeply emotional commercials. Some have taken witty looks at relationships or gender roles - like M&S' excellent "Mrs. Claus" ad for Christmas 2016. But none of the high-scoring ads have used the kind of stereotypes the ASA are gunning for. Audiences just don't like them. The new understanding of the power of emotion makes lazy ads a dangerous gamble. That's not political correctness; it's commercial common sense.

The final reason advertisers peddle stereotypes is the deliberate pursuit of shock value and publicity. They know people will find the ad offensive: they also know that will create plenty of Tweets, column inches, and maybe even TV coverage. Protein World, creators of the notorious "Beach Body" poster ad that was slammed in 2015 for promoting unrealistic body image, boasted after the fact that enquiries had increased. Sadly, this was probably true. Fame - simply getting your name and brand familiar to new customers - is a proven strategy for small, up-and-coming brands.

In the long run, though, that strategy can't last. Take a brand like GoDaddy, the website hoster whose risqué Super Bowl ads were regularly damned as sexist and voted among the year's worst. GoDaddy weren't interested in profitable growth so much as achieving as much reach as possible before an IPO, and the massive Super Bowl audience and buzz around their ads was a means to that end. Once the company went public, the cheeky ads stopped - and GoDaddy achieved its first profit.

So while shock tactics can deliver word-of-mouth for a small brand, in the long-term and for larger brands, the strategy that best leads to profitable growth is emotion. The more people feel, the more people buy. And emotional payoffs and corny stereotypes aren't really compatible. That's why it's only lazy or cynical advertisers who will be left worse off by the ASA's moves.

Tom Ewing is a senior director at System1 Group, and co-author of new book System1: Unlocking Profitable Growth. For more information see www.System1Group.com